In Search of the Giant Trees of Amapá

Por Victor Keller

17 de January de 2025

In October 2024, Geonoma participated in the project “Using plant hydraulic scaling to predict the drought vulnerability of the world’s tallest tropical trees”, coordinated by Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto de Lima Bittencourt, University of Exeter, England. This project took place in the Tumucumaque Mountains National Park, in Amapá, the largest National Park in Brazil, with more than 3.5 million hectares of extension, and the challenges for its realization were as great as the trees we would find ahead.

Geonoma’s objective in this project was to carry out a floristic and phytosociological survey (structure and composition) of the locations where the individuals of red angelim (Dinizia excelsa Ducke) and other species with giant specimens occur, which can reach heights between 40 and 75 m, inside the Park. To this end, we sampled 5 100×100 m plots over a month, totaling an area of 5 hectares in the middle of the primary Amazon rainforest.

As this is a remote area and a work with a complex methodology, which goes beyond taking standard measures and identifying the tree specimens, the planning of the work began months before we went to the field, with the support of Prof. Dr. Bittencourt and the ICMBio teams responsible for the management of the park, who mainly assisted in the logistical issues for the arrival of the field team, materials and food to keep us in the base throughout the execution of the project.

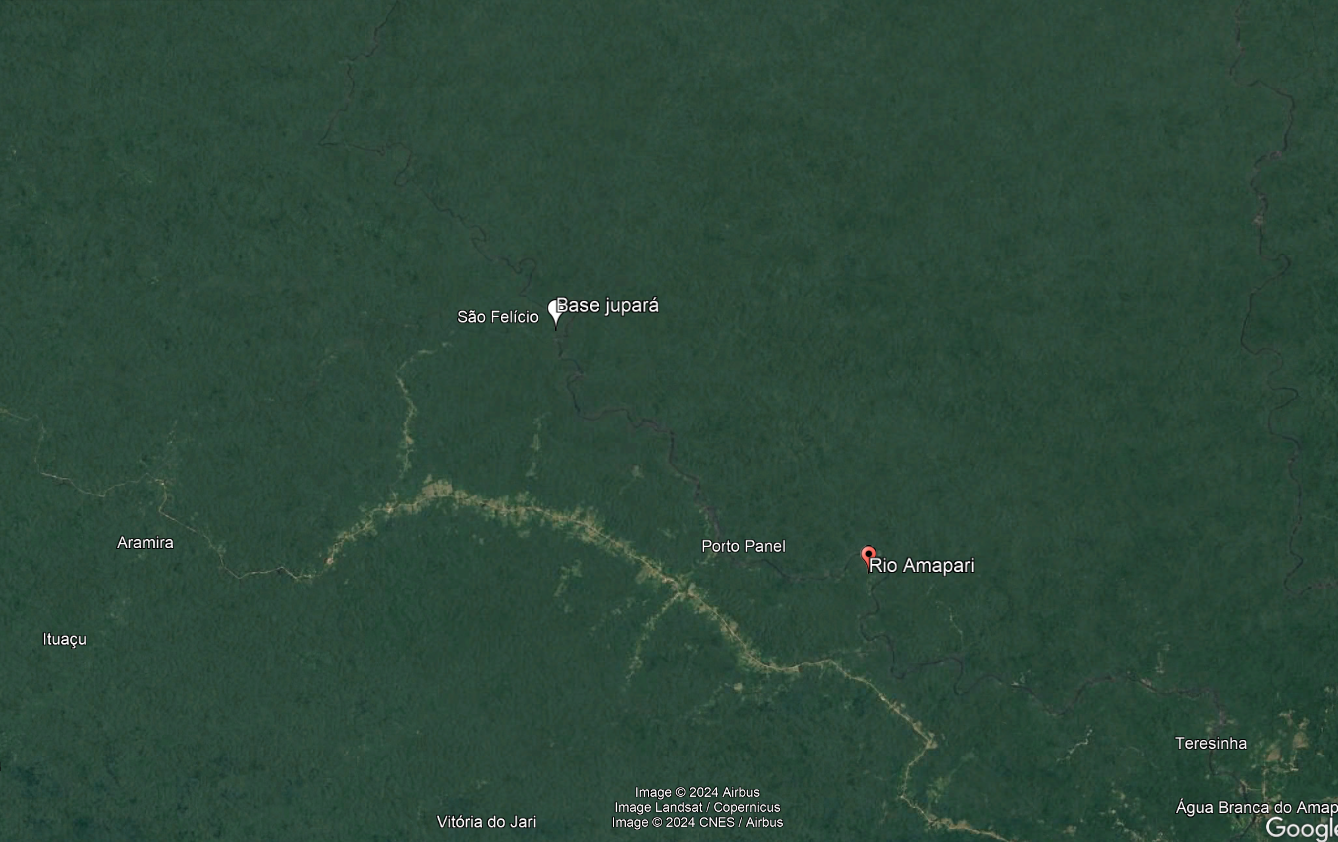

Location of the Jupará base of the Tumucumaque Mountains National Park. Wherever you look, you only see forest.

The support of ICMBio managers and technicians was also essential to compose the field team based on indications from local people who live around the Park and who participate in several research and tourism projects in the Park. Thus, in addition to a great knowledge of the Park and its surroundings, the field team also had experience in research projects with fauna and flora, which was of great value for the execution of the work with safety and technical rigor.

The field team consisted of two expert boatmen, Alvino and Aldemir, also known as Gigi, who snaked the rivers escaping the stones that could destroy the motors of the boats to take us to the sampling areas and search for supplies in Sete Ilhas, the nearest town to the Park; the cooks Patrícia and Rosana who made the best lunches and dinners in the Tumucumaque and region, always keeping the team fed and with energy for the challenges of each day; the climbers Arielton, Carlindo, Daniel, Gabriel, Junho and Robson who did not hesitate to use the climbing equipment and all their skills to access the tallest trees and collect their branches; the parabotan Amerivaldo, great connoisseur of the local flora; and the biologists Eduardo Saddi, responsible for the botanical identifications in the field and Victor Keller (Geonoma), responsible for taking the measurements of height, notes and logistics in the field. In addition to these, ICMBio analyst Christoph Jaster, former manager of PN Tumucumaque Mountains, who offered us enormous support in opening plots and in knowledge of local vegetation, and senior specialist Geza Arbocz (Geonoma), who was instrumental in preparing the pre-field logistics, and who offered great support with his experience in project management and with his deep botanical knowledge, were in the field in the first week of work.

Field team composed of botanists, climbers, boatmen and assistants.

Field crew storing climbing gear in the forest-mounted shed and preparing to return to base with a collection bag full of botanical samples.

Access to the Jupará base of the Tumucumaque Mountains PN, where we were housed, is from the Municipality of Serra do Navio, where there is an ICMBio base that supports the operation in the Park. Leaving the base, we traveled about an hour by dirt road to reach the port of Sete Ilhas, where we loaded the boats to head towards the Park. The boat trip takes about an hour and a half, being hampered by the low water level in the Amaparí River, making it necessary to get off the boats at some points to pass through the river rapids. On this path it was already possible to observe some individuals of red angelim standing out in the landscape, which increased our anxiety and expectation to see these beautiful specimens of the Brazilian flora up close.

When we arrived at the base, it was already possible to have a small sample of the exuberance of the vegetation that we would see ahead. Our accommodation was permeated by arboreal specimens that caught our attention for their great size and beauty.

In the central portion, a specimen of maçaranduba (Manilkara sp.) with more than 40 m, next to a yellow ipe (Handroanthus serratifolius (Vahl) S.Grose) with the canopy full of flowers reflecting the yellow of the sun that shines brightly every day. On the path between the trapiche and the base, an individual of pequiá (Caryocar villosum (Aubl.) Pers.) that every morning formed a carpet of white flowers on our way, and behind the cafeteria a specimen of orange (Martiodendron sp.) with imposing tabular roots.

Entering the forest for the first time to start the work, we are impressed by the size and density of the vegetation. The size, due to its grandeur, with a canopy over 30 m high and emerging specimens surpassing this mark with ease. The density, on the other hand, causes us astonishment by the distance between the arboreal individuals, forming an open understory, with the spaced presence of small bushes, palm trees (with emphasis on the comforting and constant presence of specimens of the genus Geonoma spp.) and tree trees, being possible in some points to run through the forest without being bothered by vines, branches or shrubs. The low tree density in these areas is explained precisely by the large size of the tree individuals, which occupy large areas with their large canopies, facilitating our work of moving through the forest.

Aspect of the understory, with low density of individuals, facilitating the displacement of the team in the field.

To carry out the phytosociological survey, it was first necessary to open the 1 ha plots and delimit them with PVC pipes both in their outer limit and in their interior, forming a grid with sub-plots of 20×20 m. The inclusion criterion for sampling was specimens with a Breast Height Diameter (DBH) greater than 10 cm. The height of the tree specimens was measured using a Range Finder, an electronic device that calculates the height of the trees using a laser beam. The measured tree specimens were plated and their location was marked with a GPS device.

The climbing team was essential to carry out the collections of botanical material for identification in the field and to compose the testimonies of the inventoried species. Given the great species richness observed in the areas under study, climbers barely had time to rest, climbing the trees every time a new species appeared in the inventory. Dozens of botanical materials were collected daily, with new species in the inventory appearing every day, including the last one. If on the one hand it is always very interesting to come across this great richness and diversity of species, with many novelties every day, on the other hand, this meant that we would still be a long time pressing plants after a long day in the field. Despite the fatigue, this was a time of much learning, when we could calmly look at the collected species and study their characteristics to recognize them in the field again.

Gabriel climber approaching the canopy of a tree to collect a branch that will testify to the occurrence of this species in the study area. Even with climbing training and use of all safety equipment, it takes courage.

One of the few species that did not present difficulty for its recognition in the field was the red angelim, one of the main objects of study of the project touched by Prof. Dr. Bittencourt. Their specimens stood out in the forest for their enormous size, with individuals ranging between 60 and 75 m in height, trunks with a diameter exceeding 2 m, indicating their age of hundreds of years, and a bark with large reddish plates that stood out like embers amid the green of the vegetation. Interestingly, one of the main uses for red angelim wood, in addition to civil construction, is the production of coal, mainly to feed steel kilns, potteries, and, according to our teammates, capable of holding a barbecue for hours with only a small piece of coal.

In addition to beauty and exuberance, the red angelim specimens presented a great challenge for taking their diameter and height measurements. Regarding height, it was always a challenge to find, so high on the canopy, the highest branches of the individual so that we could aim the range finder and shoot the laser that would give us the precise value of the individual’s height. As for the diameter, the red angelim specimens have tabular roots that, although not as leafy as those of a sumaúma, promote a deformation in the trunk preventing us from being able to measure the standard DAP (at 1.3 from the ground), being necessary to climb a ladder, sometimes reaching more than 6 m in height in the trunk and using a team equipped with long sticks to assist the passage of the tape measure around the trunk of the individuals.

How many people does a red angelim measure? We used a ladder to try to escape the sapopembas and the trimmer as a stick to drive the tape measure around the trunk. Some people are needed.

A survey is not only made of trees. The specimens of lianas (vines) were giant and diverse, which were also measured and included in the scope of the work, presenting stems with all types of colors and shapes, and canopies that were lost on the canopy, always on the tallest arboreal specimens present around.

The final part of our expedition involved visiting two plots that were further from the accommodation, and it was necessary to travel about half an hour by boat up the Amaparí River. During this journey, it was possible to observe different examples of flora on the riverbank, usually with different and striking flowers and fruits. In addition to the flora, we also saw numerous birds such as swallows, herons, toucans, hawks and macaws that animated our morning. Sometimes we could be graced by the presence of a flock of scent monkeys that strolled through the trees by the river. However, one of the greatest spectacles of this route was the final approach to the place where our plots were allocated. When making the last curve of the river, the ‘sanctuary of the angelins‘ was revealed in front of us, a place with a great density of individuals of red angelim where we could observe their canopies standing out over the forest canopy, forming a landscape at once imposing and exuberant, evidencing all the majesty of these trees.

Amaparí River near the sampling site of the last two plots. In the background the ‘sanctuary of the angelins’ with its crowns standing out far above the canopy.

After one month in the field, 2381 tree individuals were measured in 5 ha sampled, comprising 48 families, 127 genera and 423 morphotypes, part of them already identified and most of them in the process of identification by consulting herbaria, specialists in the different groups and consulting the specialized literature. We believe that our work, together with what has been developed by Prof. Dr. Bittencourt and his collaborators will be of great value to assist in understanding the diversity of the Amazonian flora, in understanding the physioecology behind the hydraulic functioning of giant trees and how this magnificent and exuberant flora will respond to the climate changes that are underway on the planet, and may generate subsidies that favor the conservation of these majestic and unique species and landscapes.